Exhibition “50 years of the Carnation Revolution” by Sebastião Salgado and Lélia Wanick

In February this year, upon turning 80, Sebastião Salgado told The Guardian that he would be retiring from fieldwork to dedicate himself to his monumental collection of photographs. Less than three months later, Sebastião and Lélia Wanick launched the exhibition “50 Years of the Carnation Revolution in Portugal” at the Museum of Image and Sound (MIS) in São Paulo.

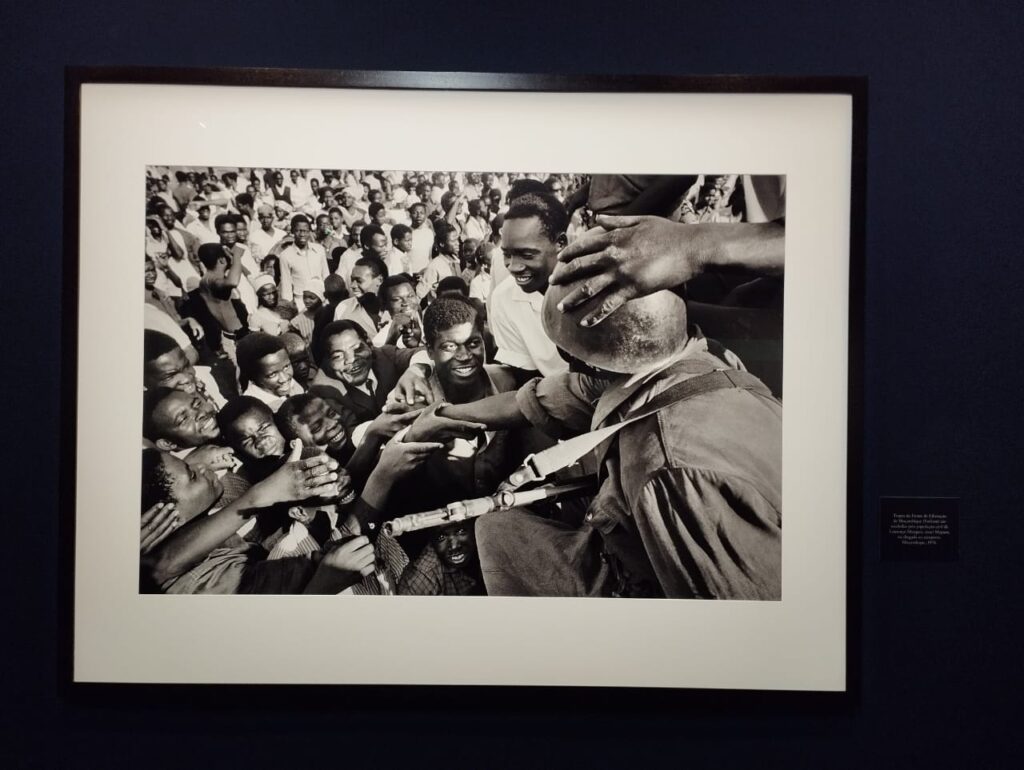

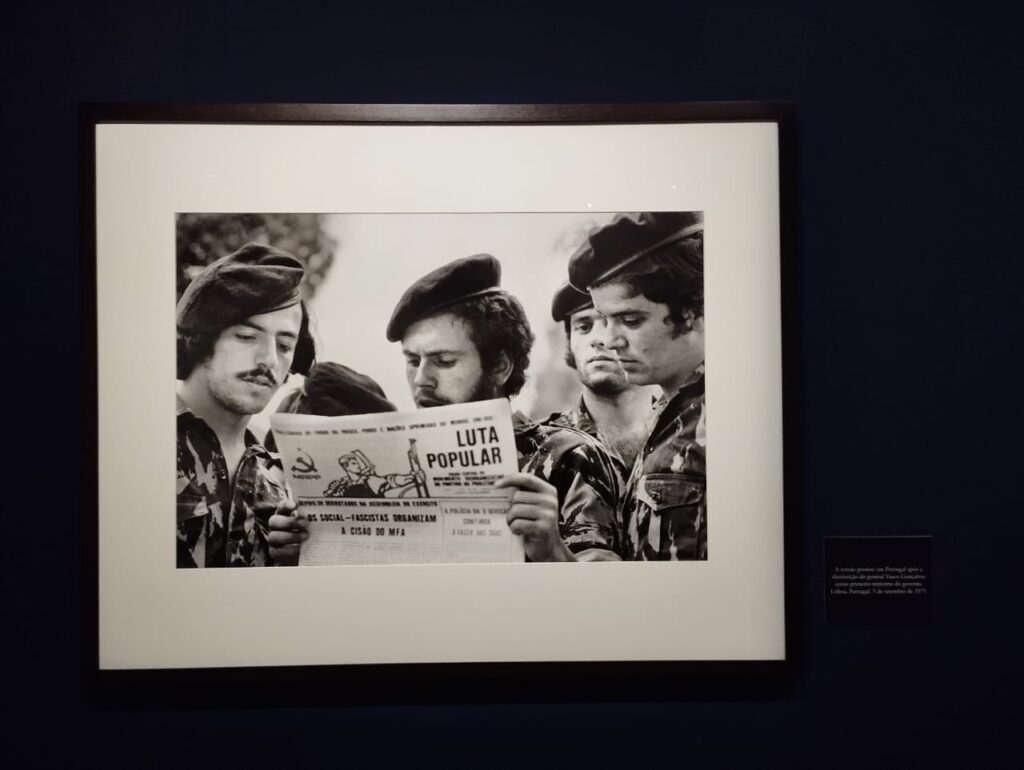

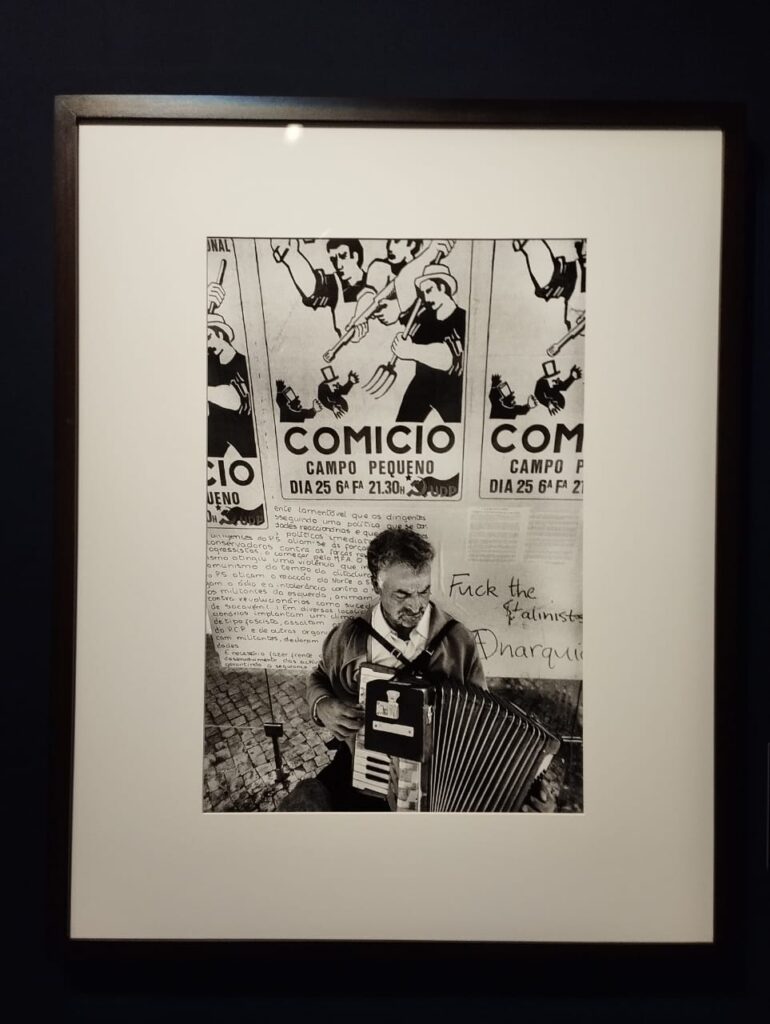

This was the couple’s first photographic work, covering the end of the Salazarist regime and the independence of Portugal’s last overseas colonies. Featuring over 50 photographs never before shown to the public, taken between 1974 and 1975, the exhibition reveals the artistic and documentary power of Salgado’s projects from the beginning of his photographic career.

Later accused by some imperialist minds of being “aesthetes of poverty,” Salgado and Wanick showed the public in the North, the center of capitalism, the trail of social and environmental destruction left by colonial exploitation in peripheral countries, as well as its consequences for the metropoles, as in the case of Portugal. But rather than criticizing Capital itself, the inexhaustible source of exploitation of Nature and people, such minds preferred to criticize those who developed the evils of this system that seeks the infinite accumulation of money in the hands of a few.

Supported by the ruling class and the clergy, the Salazarist regime was a type of fascism that survived the fall of its neighbors Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco. The popular fervor to overcome this regime, “the beloved child of the Church and Capital” like other fascist dictatorships, caught the attention of the Brazilian photographer couple, exiled in France due to the civil-military dictatorship imposed in Brazil in 1964—with the unconditional support of the White House for the suppression of Latin American democracies, and with the approval of the ruling classes and the church.

Victims of the 1964 coup, Sebastião and Lélia were enthusiastic about the Portuguese uprising and filled with hope. Perhaps the Portuguese experience could finally inspire and contribute to Brazilian progress. However, the Carnation Revolution, like any popular process, was marred by contradictions and internal disputes, which were equally documented and narrated in the 50-year exhibition. The five decades of antifascist resistance were not enough to expunge the xenophobic, nationalist, and colonialist ideology from Portugal which, like many countries in Europe

For Sebastião Salgado, Portugal of the Carnation Revolution was where he learned to construct a photographic narrative in practice. For us, learners and lovers of visual stories, the exhibition is a true lesson in history and photography. The exhibition is part of the “May of Photography” program at MIS, which includes six other exhibitions, as well as the screening of documentaries about photography.

Finally, my praise for Sebastião Salgado and Lélia Wanick’s work is not unreserved or without caveats. Just as in any popular process and any person, totality and contradiction unite, coexist, and move the being. While Salgado almost personally sacrificed to give visibility to oppressed peoples, he also used his voice to try to minimize the responsibilities of the company Vale in its socio-environmental crimes. He also verbalizes a profound disrespect for people whose only photographic means are the cameras on their mobile devices when he says and repeatedly states that with a smartphone one does not make photography. He also ignores the photographic work of the Amazonian peoples, who seek to build their own identity through their own daily documentation, when he claims that he is the only photographer documenting the Amazon in his last field project. But art and artists are inseparable elements and, with or without contradictions, the 50th-anniversary exhibition of the Carnation Revolution is impressive for its content, form, originality, and, undoubtedly, pioneering spirit after half a century of an inspiring journey.